CHINATOWN RISING: 24 Blocks of History Comes Alive

November 9, 2019

By Dr. Craig D. Reid

In 1973, when I was 16, taking 30 pills/day and in the hospital every three months, my doctor told me that I would be dead in five years due to the incurable, deadly terminal disease cystic fibrosis (CF). Not wishing to have my parents see me slowly waste away I decided to commit suicide. Days away from the end, I saw Bruce Lee’s Fists of Fury (1972; aka Big Boss) and a few seconds after his first fight began, I went from being depressed and waiting to die to wanting to live and learn what he was doing. This started me down the path of martial arts and searching for chi gong, knowing that these were my last chances to survive. Lee was also my introduction to the existence of San Francisco’s Chinatown, his birthplace, and that there was also a Chinatown in New York City.

In 1973, when I was 16, taking 30 pills/day and in the hospital every three months, my doctor told me that I would be dead in five years due to the incurable, deadly terminal disease cystic fibrosis (CF). Not wishing to have my parents see me slowly waste away I decided to commit suicide. Days away from the end, I saw Bruce Lee’s Fists of Fury (1972; aka Big Boss) and a few seconds after his first fight began, I went from being depressed and waiting to die to wanting to live and learn what he was doing. This started me down the path of martial arts and searching for chi gong, knowing that these were my last chances to survive. Lee was also my introduction to the existence of San Francisco’s Chinatown, his birthplace, and that there was also a Chinatown in New York City.

Besides martial arts, I quickly became enamored with Chinese history and after watching David Carradine’s Kung Fu on TV, wanted to learn about the plight of the Chinese in America. Beyond working on the railroads, little else of information was available for white America where I lived. However, when I attended Cornell University, where 1400 students (18% of the student body) were Asian, mostly Chinese Americans, I was excited knowing my years at Cornell would be awesome…and they were. When I was a senior at Cornell, I was the President of the Chinese Student Association and a member of the Asian American Coalition (AAC), which was mostly made up of students from NYC’s Chinatown.

Harry and Josh Chuck

Fast forward to 2019, hey, I’m still alive and on Friday night (Nov. 8) at SDAFF, I saw what in my opinion is the Holy Grail of Chinatown films, a documentary that thoroughly moved me. Directed by dad Harry Chuck and son Josh Chuck, Chinatown Rising (CR) brought back long lost memories as snippets of the film’s subject matter were things I had heard about that were discussed by the seriously inspired AAC members. To now know what they were talking about and to see it in front of my eyes…I had one question that I really wanted to ask Harry, and throughout the film my mind jockeyed back and forth, concerned that it might be insulting or out of place.

Forty five years in the making, Chinatown Rising, is a documentary that evolved from Harry’s love of film and a film project that was a Master’s Degree requirement at San Francisco State College. Armed with a 16mm camera, the SF Chinatown-born and eventual Reverend Harry flung himself into the middle of the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-1960s using Chinatown’s 24 city blocks as the canvas, the camera a brush, film footage the characters and landscapes, and finding the chi (life force) in the peoples, places and times to successfully capture their essences and tell an epic story.

Forty five years in the making, Chinatown Rising, is a documentary that evolved from Harry’s love of film and a film project that was a Master’s Degree requirement at San Francisco State College. Armed with a 16mm camera, the SF Chinatown-born and eventual Reverend Harry flung himself into the middle of the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-1960s using Chinatown’s 24 city blocks as the canvas, the camera a brush, film footage the characters and landscapes, and finding the chi (life force) in the peoples, places and times to successfully capture their essences and tell an epic story.

With son Josh’s co-directing inclusion 40 years later, a new sense of purpose arose. While piecing together the 10 hours of footage Harry shot back then…demonstrations, interviews with community activists, marches, footage of himself verbally challenging the man (authority figures; Asian and white), teen/young adult identity crises, when the Black Panthers were in Chinatown supporting the Chinese Americans right to fight, the rise of youth interest in Mao Tse Tung, the police beatings, the frustrations of Chinatown youth, the community divides between self determination and the status quo of the Chinese elders and more…CR becomes a tool for Harry to tell Josh about the past. Harry was essentially making sure that the new generation of Chinese Americans would understand the struggles of their Chinese American heritage, and by doing so, it would not be forgotten.

With son Josh’s co-directing inclusion 40 years later, a new sense of purpose arose. While piecing together the 10 hours of footage Harry shot back then…demonstrations, interviews with community activists, marches, footage of himself verbally challenging the man (authority figures; Asian and white), teen/young adult identity crises, when the Black Panthers were in Chinatown supporting the Chinese Americans right to fight, the rise of youth interest in Mao Tse Tung, the police beatings, the frustrations of Chinatown youth, the community divides between self determination and the status quo of the Chinese elders and more…CR becomes a tool for Harry to tell Josh about the past. Harry was essentially making sure that the new generation of Chinese Americans would understand the struggles of their Chinese American heritage, and by doing so, it would not be forgotten.

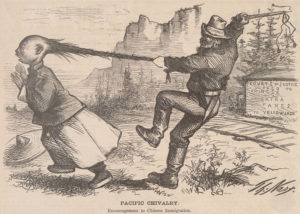

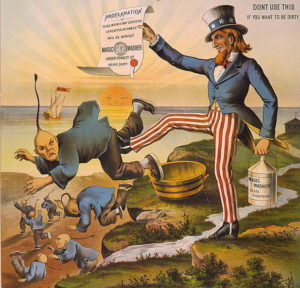

For those that came in late, in the 1850s, Chinese immigrants were admired for their moral codes, generosity and being hard-working, but in 1852, California governor John Bigler raised hate and fear by fabricating, “Five hundred came last week, 1000 on the way, 20000 line ports waiting to come to be paid $4/month and bring slavery to California.” His leaflets gave people permission to attack Chinese. In the 1860s, due to America wanting China trade, the gold rush and railroad building, Chinese male immigrants increased. When the Chinese were labeled as a degrading inferior race, race riots erupted. Whites and Mexicans mass lynched Chinese in 1871 Los Angeles. The punishment for killing a Chinaman back then was a $12.00 fine. The Page Act of 1875 banned Chinese women immigrants, its goal to have the Chinese population die-off. As the Chinese men to women ratio grew (20:1 by 1880), the Tongs splintered and got into prostitution, protection rackets, and ran opium and gambling dens. In 1876, the Workingmen party (WP) founded by a naturalized Irishman and created a “Chinese must go” policy to purge the Chinese in the name of ethnic white purity.

For those that came in late, in the 1850s, Chinese immigrants were admired for their moral codes, generosity and being hard-working, but in 1852, California governor John Bigler raised hate and fear by fabricating, “Five hundred came last week, 1000 on the way, 20000 line ports waiting to come to be paid $4/month and bring slavery to California.” His leaflets gave people permission to attack Chinese. In the 1860s, due to America wanting China trade, the gold rush and railroad building, Chinese male immigrants increased. When the Chinese were labeled as a degrading inferior race, race riots erupted. Whites and Mexicans mass lynched Chinese in 1871 Los Angeles. The punishment for killing a Chinaman back then was a $12.00 fine. The Page Act of 1875 banned Chinese women immigrants, its goal to have the Chinese population die-off. As the Chinese men to women ratio grew (20:1 by 1880), the Tongs splintered and got into prostitution, protection rackets, and ran opium and gambling dens. In 1876, the Workingmen party (WP) founded by a naturalized Irishman and created a “Chinese must go” policy to purge the Chinese in the name of ethnic white purity.

Of note, founded by Lo Yet, circa 1853, the first SF Tong (translation, meeting hall), the Chee Kong Tong, in 1885 hosted a Chinese dissident in America, taught him democracy and introduced the Ming-derived down with the Manchus slogan. The 18-year-old was Sun Yat-sen. In 1877, the Tong Wars afoot, Sen. James Blaine introduces the 15-Passenger Act (limit of 15 Chinese on a ship entering America) expounding, “Are we the Kingdom of Christ or the Kingdom of Confucius?”

On May 6, 1882, Republican President Chester Arthur’s signed the Chinese Exclusion Act (CEA) into law. It’s the only time in American history that singled out a specific race and nationality with a law that made it illegal for Chinese workers to come to America and Chinese nationals already living here to become U.S. citizens. Originally meant for 10 years, the CEA was enforced for 60 years. Why? Chinese were considered undesirables, an inferior race, corrupt and rumors said that they refused to assimilate into the American mainstream. Also, their food, culture, appearance and Gods were too different and due to their hygienic and sanitation practices they could breed and spread disease across America.

Lucinda Lee-Katz

Cutting back and forth between interviews with Harry, an army of community activists such as Phil Chu, Philip Choy, Laureen Chew, Reverend Norman Fong, Fred Lau and Lucinda Lee-Katz, and film/news clips from a local TV station, CR timelines critical events that shaped social change in Chinatown, the starting point being President Lyndon B. Johnson’s enactment of his 1965 Immigration and Naturalization act.

With time passages, events elevated as ironically each battle Chinatown faced were all some form an exclusion act such as: the San Francisco State Student Strike of 1968-69, which college president S.I. Hayakawa adversely opposed, yet the end result saw the eventual formation of Ethnic Studies at the school; the negative attitude of the Chinese Six Company against the student movement; the San Francisco school strike and school integration in San Francisco; increases in Chinatown crime; Fred Lau becoming the first Chinese American cop accepted into the Chinatown Squad; the intimidating and fear inducing assassination of the young community worker Barry Fong-Torres;

With time passages, events elevated as ironically each battle Chinatown faced were all some form an exclusion act such as: the San Francisco State Student Strike of 1968-69, which college president S.I. Hayakawa adversely opposed, yet the end result saw the eventual formation of Ethnic Studies at the school; the negative attitude of the Chinese Six Company against the student movement; the San Francisco school strike and school integration in San Francisco; increases in Chinatown crime; Fred Lau becoming the first Chinese American cop accepted into the Chinatown Squad; the intimidating and fear inducing assassination of the young community worker Barry Fong-Torres;

the street gang invoked Golden Dragon (restaurant) Massacre; the playground incident led by Harry where he saved a popular landmark playground from territory stealing real estate moguls; the unsuccessful battle to prevent mass eviction from the Filipino owned International Hotel that bordered Chinatown; and the decade struggle for affordable housing in Chinatown where for the first time in years, the Chinatown youth and elderly marched as one to support the building of the Mei Lun Yuen, it’s purpose to provide housing relief for many families and the elderly.

the street gang invoked Golden Dragon (restaurant) Massacre; the playground incident led by Harry where he saved a popular landmark playground from territory stealing real estate moguls; the unsuccessful battle to prevent mass eviction from the Filipino owned International Hotel that bordered Chinatown; and the decade struggle for affordable housing in Chinatown where for the first time in years, the Chinatown youth and elderly marched as one to support the building of the Mei Lun Yuen, it’s purpose to provide housing relief for many families and the elderly.

As it were, just as the board of HUD supervisors was about to nix the project, because folks were complaining that it would block their apartment views of the city, Chinatown’s last chance hope was when Harry presented to the board a five-minute short film he had put together revealing the dilapidated housing and squalid living conditions that families were enduring. The film short spoke louder than words, just as Chinatown Rising is doing today.

As it were, just as the board of HUD supervisors was about to nix the project, because folks were complaining that it would block their apartment views of the city, Chinatown’s last chance hope was when Harry presented to the board a five-minute short film he had put together revealing the dilapidated housing and squalid living conditions that families were enduring. The film short spoke louder than words, just as Chinatown Rising is doing today.

At the end of the screening my mind returns to the battle between should I ask Harry the question. Throughout the Q&A of Harry and Josh, the discussion’s direction didn’t offer a segway into what I wanted to ask. Time ran out and we had to leave the theater. Harry was quickly surrounded by folks hoping to get in a word. Streaming out into the hallway, lagging behind, I was hoping that there might be a split second to catch his attention.

Harry Chuck

The moment arrived. Introducing myself and my involvement with the Chinese students at Cornell, I apologized that my question might be out of place or have no relevancy to his film. He nodded go ahead.

“How was Bruce Lee viewed by Chinatown back then?”

Harry answers, “That…is a very interesting question. He was a hero. And today we need a hero like that.”

Though living on the edge of death and martial arts training prevented me from ever becoming a punk, I was feeling lucky that I saw Chinatown Rising, and so to you Harry and all the activists that shared their stories, you are the heroes…and you made my day.

tweet

tweet share

share